New genetically modified crops could make superweeds even stronger

By Brandon Keim

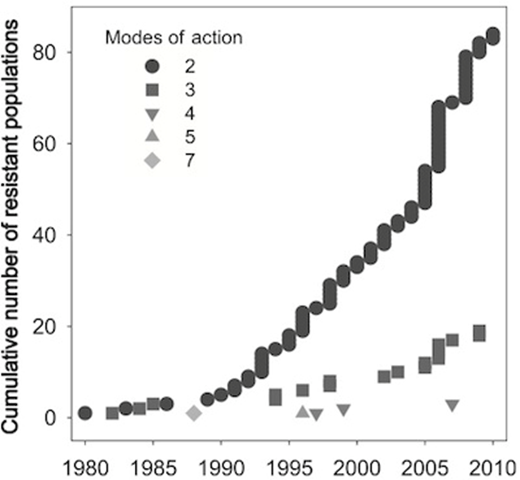

1 May 2012 Herbicide-resistant superweeds threaten to overgrow U.S. fields, so agriculture companies have genetically engineered a new generation of plants to withstand heavy doses of multiple, extra-toxic weed-killing chemicals. It’s a more intensive version of the same approach that made the resistant superweeds such a problem — and some scientists think it will fuel the evolution of the worst superweeds yet. These weeds may go a step further than merely being able to survive one or two or three specific weedkillers. The intense chemical pressure could cause them to evolve resistance that would apply to entire classes of chemicals. “The kind of resistance we’ll select for with these kinds of crops will be different from what we’ve seen in the past,” said agroecologist Bruce Maxwell of Montana State University. “They’ll select a kind of resistance that’s more metabolism-based, and likely resistant to everything.” Next-generation biotech crops erupted into controversy with the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s ongoing review of Enlist, a Dow-manufactured corn variety endowed with genes that let it tolerate high doses of both glyphosate, an industry-standard herbicide better known as Roundup, and a decades-old herbicide called 2,4-D. Back in the mid-1990s, when so-called Roundup Ready seed strains first allowed farmers to spray the herbicide directly onto fields without fear of damaging crops, 2,4-D and other older chemicals were already falling from favor. They were more toxic and less effective than glyphosate, and farmers gladly replaced them with a single all-purpose treatment. Roundup Ready varieties now account for 90 percent of U.S. soybeans and 70 percent of corn and cotton, and the pipeline for new herbicidal chemicals is mostly empty. But reliance on a single chemical came at a price: Though industry scientists predicted that weeds wouldn’t become resistant to glyphosate, more than a dozen species have done exactly that. These superweeds now infest 60 million acres of U.S. farmland, a fast-growing number that foreshadows a time when agriculture’s front-line weedkiller is largely useless. Enlist, which Dow estimates will save $4 billion in superweed-related farm losses by 2020, represents the industry’s main response to the problem: Bringing back old chemicals in new ways. Of 20 genetically engineered crops under federal regulatory consideration, 13 are designed to resist multiple herbicides. They suggest a future in which more farmland is treated with more herbicides in ever-higher doses, and have been criticized by activists and researchers worried about possible chemical dangers to human and environmental health. Largely overshadowed in the health furor, however, is the issue of new superweeds: If glyphosate-drenched Roundup Ready fields were evolutionary crucibles that favored the emergence of new, glyphosate-resistant weed strains that threaten multi-billion-dollar damage, what might new herbicide regimes create? “Resistance happens, particularly when the selection pressure is largely from one or two tactics,” said weed ecologist David Mortensen of Penn State University. “Plants are wired to protect themselves from troublesome compounds in some interesting ways.” […]