Japan leaders fret over today’s nuclear shutdown – No nukes for first time in 42 years – Thousands march against nuclear power

By MARTIN FACKLER

3 May 2012 OSAKA, Japan – Barring an unexpected turnaround, Japan on Saturday will become a nuclear-free nation for the first time in more than four decades, at least temporarily. Japan’s leaders have made increasingly desperate attempts in recent months to avoid just such a scenario, trying to restart plants shut for routine maintenance and kept that way while they tried to convince a skittish public that the reactors were safe in the wake of last year’s nuclear catastrophe. But the government has run up against a crippling public distrust that recently found a powerful voice in local leaders who are orchestrating a rare challenge to Tokyo’s centralized power. As the last of 50 functional commercial reactors is set to go offline Saturday, that local resistance to turning plants back on has confronted Japan’s leaders with a grim scenario: with the nation’s once vaunted balance of trade already deteriorating, they now face the looming prospect of summer power shortages that could drive still more factories to close or move abroad. Halting all the reactors “would be something like a group suicide,” said Yoshito Sengoku, acting chief of the governing Democratic Party’s policy committee. The showdown between local and national leaders has played out in recent weeks at a plant in Ohi, near Osaka, which the government of Prime Minister Yoshihiko Noda has set up as a crucial test case of Japan’s nuclear future. Two reactors at the idled plant were the first to pass simulated stress tests meant to show that most reactors, unlike those at the Fukushima plant devastated in last year’s earthquake and tsunami, could withstand similar disasters. The administration trusted that Ohi’s reactors would be back in operation by now, or at least would receive local approval to start up soon. Instead, the central government has found itself battling an improbable adversary: Osaka’s mayor, Toru Hashimoto, the young, plain-speaking son of a yakuza gangster who has ridden Japan’s loss of faith in government to become, seemingly overnight, the country’s best liked politician, according to recent polls. He has won widespread public support by giving voice to deep-seated public suspicions that the Tokyo government is rushing to promote the interests of the powerful nuclear industry at the expense of public safety — a situation that many Japanese now blame for leaving the Fukushima Daiichi plant so vulnerable in the first place. Mr. Hashimoto’s ascent — and his success in blocking a quick restart of the Ohi plant — are some of the clearest signs yet that the distrust generated by the government’s handling of the Fukushima disaster is reshaping attitudes in Japan, where people had long accepted Tokyo’s sway over their lives. And the Noda administration’s failure to see Mr. Hashimoto coming, along with its reliance on stress tests even as their soundness was questioned, suggests that the disconnect between the government and its people that opened with the nuclear disaster has only widened. “The Japanese public is fed up with business as usual, and Mr. Hashimoto has been able to seize on that anger,” said Wataru Kitamura, a professor of government at Osaka University. “Japan is deeply frustrated by its own political paralysis, and many see him as the answer.” Mr. Hashimoto takes pains to say he is not against nuclear power. He is, instead, against the opaque, top-down authority that has characterized Japan’s postwar rise and that many Japanese now blame for the government’s perceived failure to prevent last year’s accident and fully inform the public of the radiation risks it posed. That same attitude apparently led national leaders to underestimate how difficult it would be to convince local leaders to restart the reactors. “How can they make a decision like this behind closed doors, without explaining it to the Japanese people?” said Mr. Hashimoto, 42, who set up his city’s own independent panel of experts to look into safety measures at the plant, 55 miles north of here. “The restart issue reveals the flaws of Japan’s current system, and how it is beholden to special interests.” Mr. Hashimoto has succeeded in holding up the restart partly because this city of 2.7 million is not only the biggest customer of the Ohi plant, but also the biggest shareholder of the plant’s operator, Kansai Electric Power. But Mr. Hashimoto may prove to be a longer-term danger to Tokyo’s leadership if other local officials nationwide follow his lead in demanding more answers before allowing their own nearby plants to start up again. […]

Japan’s Leaders Fret as Nuclear Shutdown Nears

By arevamirpal::laprimavera

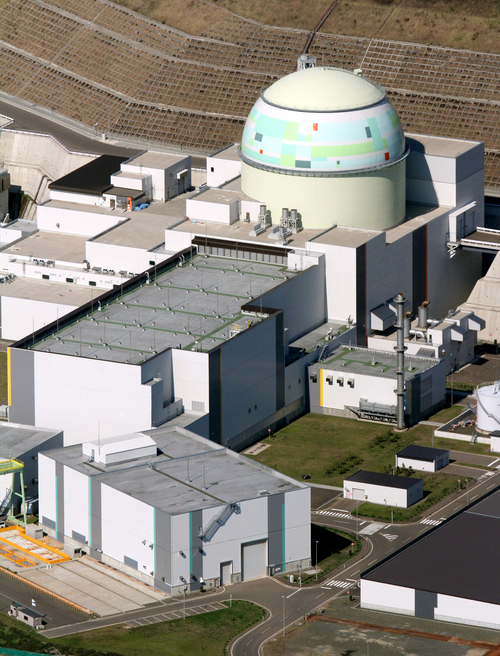

5 May 2012 Reactor 3 at Tomari Nuclear Power Plant in Hokkaido will be shut down for the scheduled maintenance around midnight on May 5. Tomari’s Reactor 3 is a Pressurized Water Reactor that started operation in 2009. Tomari Nuclear Power Plant is one of the newer nuclear power plants in Japan; the first reactor started operation in 1989. Reactor 3 plans to start using MOX fuel, but a third-party investigation revealed that the plant operator Hokkaido Electric (HEPCO) had used “shills” in one of the “town hall meetings” for the local residents in July last year to speak favorably of and promote the use of MOX fuel (according to the company announcement in October last year). Hokkaido’s governor Harumi Takahashi is a former career bureaucrat in the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, and she wants to restart the nuclear plant as soon as possible. […] The number of nuclear reactors in Japan is now 50, after four reactors (1, 2, 3 and 4) at Fukushima I Nuclear Power Plant have been formally declared for decommissioning. Kansai Electric has been warning the planned blackouts if Ooi Nuclear Power Plant is not restarted by summer. Anti-nuclear net citizens are saying, “Bring it on!”

By Yuri Kageyama, Associated Press

May 5, 2012 TOKYO – Thousands of Japanese marched to celebrate the switching off of the last of their nation’s 50 nuclear reactors Saturday, waving banners shaped as giant fish that have become a potent anti-nuclear symbol. Japan was without electricity from nuclear power for the first time in four decades when the reactor at Tomari nuclear plant on the northern island of Hokkaido went offline for mandatory routine maintenance. After last year’s March 11 quake and tsunami set off meltdowns at the Fukushima Dai-ichi plant, no reactor halted for checkups has been restarted amid public worries about the safety of nuclear technology. “Today is a historic day,” Masashi Ishikawa shouted to a crowd gathered at a Tokyo park, some holding traditional “koinobori” carp-shaped banners for Children’s Day that have become a symbol of the anti-nuclear movement. “There are so many nuclear plants, but not a single one will be up and running today, and that’s because of our efforts,” Ishikawa said. The activists said it is fitting that the day Japan stopped nuclear power coincides with Children’s Day because of their concerns about protecting children from radiation, which Fukushima Dai-ichi is still spewing into the air and water. The government has been eager to restart nuclear reactors, warning about blackouts and rising carbon emissions as Japan is forced to turn to oil and gas for energy. […] The crowd at the anti-nuclear rally, estimated at 5,500 by organizers, shrugged off government warnings about a power shortage. If anything, they said, with the reactors going offline one by one, it was clear the nation didn’t really need nuclear power. […] Yoko Kataoka, a retired baker who was dancing to the music at the rally waving a small paper carp, said she was happy the reactor was being turned off. “Let’s leave an Earth where our children and grandchildren can all play without worries,” she said, wearing a shirt that had, “No thank you, nukes,” handwritten on the back.