Environmental toxins cause ovarian disease across generations

By Eric Sorensen, WSU science writer

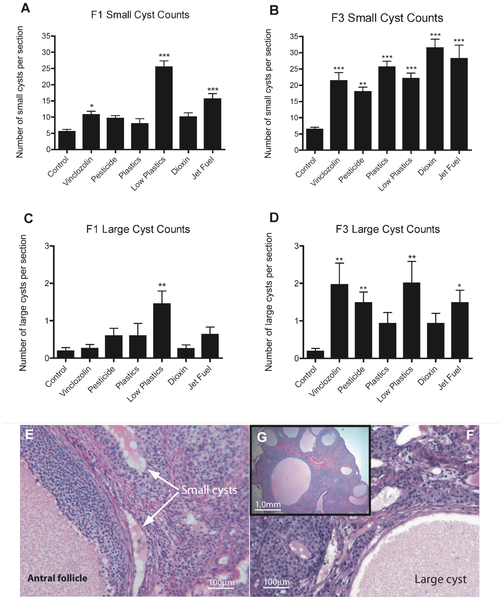

3 May 2012 PULLMAN, Washington – Washington State University researchers have found that ovarian disease can result from exposures to a wide range of environmental chemicals and be inherited by future generations. WSU reproductive biologist Michael Skinner and his laboratory colleagues, including Eric Nilsson and Carlos Guerrero-Bosagna, looked at how fungicide, pesticide, plastic, dioxin, and hydrocarbon mixtures affected a gestating rat’s progeny for multiple generations. They saw subsequent generations inherit ovarian disease by “epigenetic transgenerational inheritance.” Epigenetics regulates how genes are turned on and off in tissues and cells. Three generations were affected, showing fewer ovarian follicles – the source of eggs – and increased polycystic ovarian disease. The findings suggest ancestral environmental exposures and epigenetics may be a significant added factor in the development of ovarian disease, Skinner said. “What your great grandmother was exposed to when she was pregnant may promote ovarian disease in you, and you’re going to pass it on to your grandchildren,” he said. “Ovarian disease has been increasing over the past few decades to affect more than 10 percent of the human female population, and environmental epigenetics may provide a reason for this increase.” The research appears in the current issue of the online journal PLoS ONE. It marks the first time researchers have shown that a number of different classes of environmental toxicants can promote the epigenetic inheritance of ovarian disease across multiple generations. Research by Skinner and colleagues published earlier this year in PLoS ONE showed jet fuel, dioxin, plastics and the pesticides DEET and permethrin can promote epigenetic inheritance of disease in young adults across generations. The work is a departure from traditional studies on several fronts. Where most genetic work looks at genes as the ultimate arbiters of inheritance, Skinner’s lab has repeatedly shown the impact of environmental epigenetics on how those genes are regulated. The field already is changing how one might look at toxicology, public health and biology in general. The new study, Skinner said, provides a proof of concept that ancestral environmental exposures and environmental epigenetics promote ovarian disease and can be used to further diagnose exposure to toxicants and their subsequent health impacts. It also opens the door to using epigenetic molecular markers to diagnose ovarian disease before it occurs so new therapies could be developed.

In a broader sense, the study shows how epigenetics can have a significant role in disease development and life itself. Funding for the study was provided by the U.S. Department of Defense’s Telemedicine and Advanced Technology Research Center and the National Institutes of Health’s National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. The paper, “Environmentally Induced Epigenetic Transgenerational Inheritance of Ovarian Disease,” can be viewed here.