Massive volcanoes, meteorite impacts delivered one-two death punch to dinosaurs

By Morgan Kelly

17 November 2011 A cosmic one-two punch of colossal volcanic eruptions and meteorite strikes likely caused the mass-extinction event at the end of the Cretaceous period that is famous for killing the dinosaurs 65 million years ago, according to two Princeton University reports that reject the prevailing theory that the extinction was caused by a single large meteorite. Princeton-led researchers found that a trail of dead plankton spanning half a million years provides a timeline that links the mass extinction to large-scale eruptions of the Deccan Traps, a primeval volcanic range in western India that was once three-times larger than France. A second Princeton-based group uncovered traces of a meteorite close to the Deccan Traps that may have been one of a series to strike the Earth around the time of the mass extinction, possibly wiping out the few species that remained after thousands of years of volcanic activity.

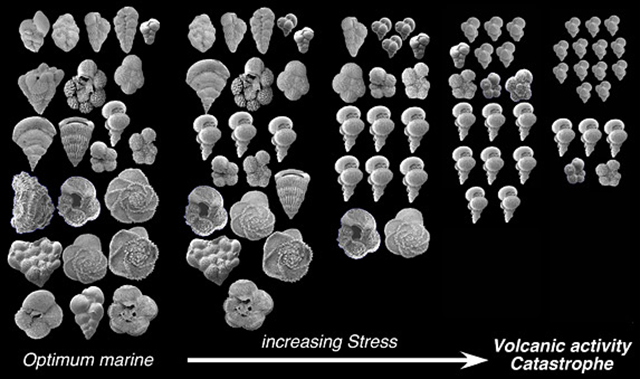

Researchers led by Princeton Professor of Geosciences Gerta Keller report this month in the Journal of the Geological Society of India that marine sediments from Deccan lava flows show that the population of a plankton species widely used to gauge the fallout of prehistoric catastrophes plummeted nearly 100 percent in the thousands of years leading up to the mass extinction. This eradication occurred in sync with the largest eruption phase of the Deccan Traps — the second of three — when the volcanoes pumped the atmosphere full of climate-altering carbon dioxide and sulfur dioxide, the researchers report. The less severe third phase of Deccan activity kept the Earth nearly uninhabitable for the next 500,000 years, the researchers report. A substantially weaker first phase occurred roughly 2.5 million years before the second-phase eruptions.

Another group based in Keller’s lab found evidence in Indian sediment of a meteorite strike from the time of the mass extinction that would have been sufficient to finish off the few but weakened species that survived the Deccan eruptions, according to a report in the journal Earth and Planetary Science Letters (EPSL) in October. This same sediment — located in Meghalaya, India, more than 600 miles east of the Deccan Traps —portrayed the Earth during this period as a harsh environment of acid rain and erratic global temperatures.

Taken together, Keller said, the Princeton findings could finally put to rest the theory that the mass-extinction event — known as the Cretaceous-Tertiary, or KT, for the periods it straddles — was triggered solely by a large meteorite impact near Chicxulub in present-day Mexico. That impact — which occurred around the time of the second-phase Deccan eruptions — is thought to have been 2 million times more powerful than a hydrogen bomb and generated an enormous dust cloud and gases that radically altered the climate. Keller has long held that the Chicxulub impact was not catastrophic enough to cause the KT mass extinction — the newest work from her lab, however, shows that the largest Deccan eruptions were.

“Our work in Meghalaya and the Deccan Traps provides the first one-to-one correlation between the mass extinction and Deccan volcanism,” said Keller, who is lead author of the Geological Society paper and second author of the EPSL paper after lead author Brian Gertsch, who earned his Ph.D. from Princeton in 2010. Gertsch is now a postdoctoral researcher at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

“We demonstrate a clear cause-and-effect relationship that these massive volcanic eruptions were far more destructive than previously thought and could have caused the KT mass extinction even without the addition of large meteorite impacts,” Keller said. “But given the environmental instability caused by the massive Deccan eruptions, an impact could easily have killed off the few survivor species at the end of the Cretaceous. It would have been a double whammy.” […]

Massive volcanoes, meteorite impacts delivered one-two death punch to dinosaurs