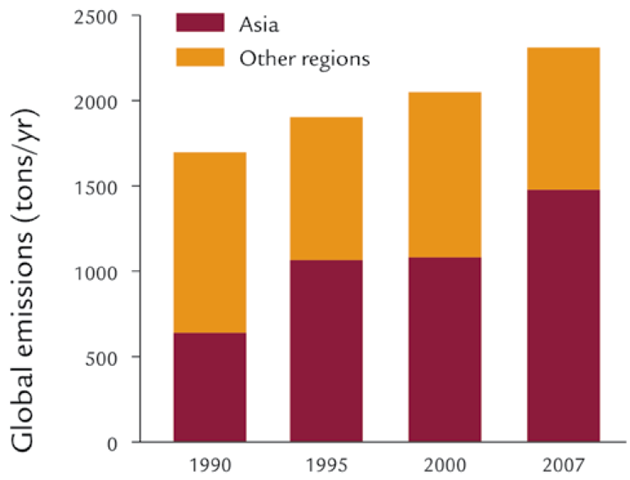

Graph of the Day: Global Mercury Emissions from Human Activities, 1990-2007

The elemental form of mercury is not as toxic to humans and wildlife as the organic form of mercury, methylmercury, which can accumulate in blood, feathers, and fur. An inorganic element found in the earth’s crust, mercury is naturally released into the environment through geological events such as volcanic eruptions. Elemental mercury (abbreviated Hg, from the Greek hydrargyrum, meaning watery silver) is the recognizable silvery liquid metal that was historically used in thermometers and industrial processes like mining gold and milling textiles. Presently, coal-fired power plants release mercury into the environment through their emissions. Since this concentrated mercury has global reach and can remain in the atmosphere for many months, it may become a significant environmental contaminant. Methylmercury is formed by bacteria that thrive in low- oxygen environments such as lake bottoms, moist soil, or even within a leaf. Organisms that feed in these wet environments ingest the methylmercury, which accumulates and concentrates up through the food web—the higher up in the web, the more potentially harmful the mercury is. Because methylmercury can accumulate over time, older individual animals may have more mercury than young animals. While mercury was once thought to be limited to fish-eating birds that live on or near water, scientists now know that insect-eating birds are also at risk. Invisible and insidious, methylmercury has been shown to adversely affect the nervous, reproductive, and endocrine systems of both humans and wildlife. Common loons are considered reliable indicators of mercury pollution in lakes. As large, long-lived birds that feed nearly exclusively on fish and tend to nest on nutrient-poor lakes, loons have been identified as one of the most important indicators of the health of an aquatic environment. BRI’s mercury studies began with loons, however, scientists soon realized that any wildlife feeding on the same lakes could be at risk for contamination. As BRI found ways to expand its work to include a variety of species, the programs began to build.