Blood levels of flame-retardant chemicals doubling every few years in North Americans

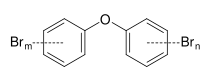

Over the past 40 years, a class of chemicals with the tongue-twisting name of halogenated flame retardants has permeated the lives of people throughout the industrialized world. These synthetic chemicals — used in electronics, upholstery, carpets, textiles, insulation, vehicle and airplane parts, children’s clothes and strollers, and many other products — have proven very effective at making petroleum-based materials resist fire. Yet many of these compounds have also turned out to be environmentally mobile and persistent — turning up in food and household dust — and are now so ubiquitous that levels of the chemicals in the blood of North Americans appear to have been doubling every two to five years for the past several decades. Acting on growing evidence that these flame retardants can accumulate in people and cause adverse health effects — interfering with hormones, reproductive systems, thyroid and metabolic function, and neurological development in infants and children — the federal government and various states have limited or banned the use of some of these chemicals, as have other countries. Several are restricted by the Stockholm Convention on persistent organic pollutants. Many individual companies have voluntarily discontinued production and use of these compounds. Yet despite these restrictions, evidence has emerged in recent months that efforts to curtail the use of such flame retardants — a $4 billion-a-year industry globally — and to limit their impacts on human health may not be succeeding. This spring and summer, a test of consumer products, as well as a study in Environmental Science & Technology, showed that use of these chemicals continues to be widespread and that compounds thought to be off the market due to health concerns continue to be used in the U.S., including in children’s products such as crib mattresses, changing table pads, nursing pillows, and car seats. Also this summer, new research provided the first strong evidence that maternal exposure to a widely used type of flame retardant, known as PBDEs (polybrominated diphenyl ethers), can alter thyroid function in pregnant women and children, result in low birth weights, and impair neurological development. “Of most concern are developmental and reproductive effects and early life exposures — in utero, infantile and for children,” Linda Birnbaum, director of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and the National Toxicology Program, said in an interview. […] In one study, published this summer in the American Journal of Epidemiology, University of California, Berkeley researchers found that each ten-fold increase in levels of various brominated flame retardants in a mother’s blood was associated with an approximately 115 gram decrease in her baby’s birth weight, a drop the researchers describe as “relatively large.” […]