Deer, pronghorn numbers in severe decline in Colorado, Wyoming as demands on public lands rise

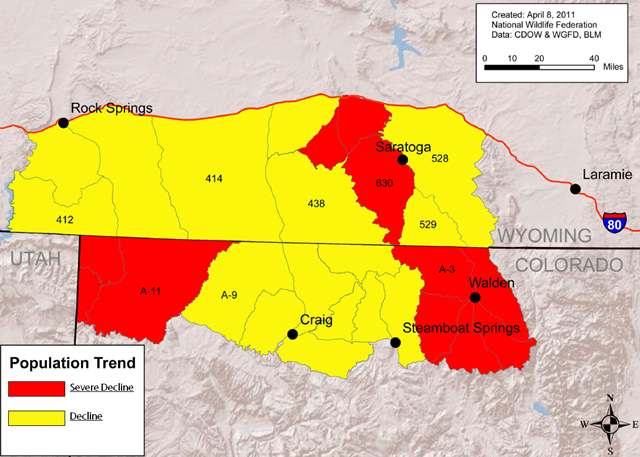

August 10 (NWF) – Populations trends are declining for mule deer and pronghorn antelope herds on both sides of the Colorado-Wyoming border and herds may not be able to fully recover unless federal and state agencies act to protect core habitats, according to a report released today by the National Wildlife Federation. “We are seeing a slow, inexorable decline in populations of both species and a corresponding decline in hunting opportunities in both states,” said Steve Torbit, NWF’s regional executive director. “If we are to maintain our native deer and pronghorn populations and our hunting traditions, land managers and wildlife agencies need to address the landscape-wide impacts that undermine the habitat vitality wildlife relies on.” The U.S. Bureau of Land Management, which has jurisdiction over almost all of the West’s vast federal lands, has management responsibility that stretch across state lines and over the interior Rocky Mountain West. “The BLM must recognize the cumulative, landscape-wide impacts of its decisions and that a lease or permit granted in one area or state can directly result in added stress to migrating game herds in an adjacent state,” Torbit said. “The needs of wildlife over the entire landscape need to be fully factored in before permits for oil, gas, wind farms, agricultural practices or any other human activity are permitted.” The report, “Population Status and Trends of Big Game along the Colorado/Wyoming State Line,” was prepared by veteran wildlife biologists John Ellenberger and Gene Byrne. Rather than look at only the most recent data, Byrne and Ellenberger analyzed wildlife agency statistics collected over the past 30 years, including population, hunter harvest and hunting license trends. Statistics for game management units in both states were reviewed in an area roughly bounded by Interstate 80 on the north, the Green River to the west, U.S. Highway 40 on the south and Laramie, WY and Walden, Co on the east. “The information we analyzed clearly shows steady population declines in both states for many of the deer and pronghorn herds that we examined,” Ellenberger said. “We are concerned that at some point, the resiliency of these herds to recover will be lost, creating a situation where we can only expect further declines,” Ellenberger explained. “It is our professional opinion that federal land managers need to consider the full impact their decisions about development will have on our native wildlife or we risk further declines in our wildlife resources. “Evaluations of impacts to wildlife and wildlife habitat need to be performed at the landscape level, not just localized impacts,” Ellenberger said. Both Torbit and Ellenberger emphasized that a growing body of peer-reviewed research has shown that the cumulative impacts of energy development, human population growth and agricultural practices have limited the natural resiliency of the habits wildlife need to survive. When natural factors such as periodic drought or disease affect a herd, the human impacts pile on top of each other, becoming “additive.” The result can be cumulative, potentially long-term declines. “When there is a drop in the density of animals in an area that usually results in an increase in the productivity of a herd and the recruitment of young animals” Ellenberger explained. “”If that doesn’t occur, then there are serious issues with habitat limitations.” For wildlife managers, “low recruitment” means that too few young animals are surviving to adulthood. Typically, populations of deer, pronghorn and other native species recover quickly to herd declines caused by drought or changes in habitat as soon as that specific factor is removed. For example, in the area in and around Yellowstone National Park in the late 1980s, the big-game populations suffered dramatic declines due to severe drought and the largest fire in the park’s recorded history. But within two years, the game populations were increasing thanks to adequate moisture and flourishing habitat. Some area residents have suggested that predators such as coyotes are the reason for declines. But, who has worked extensively in both Wyoming and Colorado, emphasized that pronghorn and mule deer herds have always lived with predators. “These game herds evolved with five different predators: wolves, grizzly bears, black bears, mountain lions and coyotes, and they still thrived,” Torbit noted. “We now have only three of these predators along the border with grizzlies and wolves no longer present. “What’s changed are the intense demands we are placing on Western landscapes,” Torbit explained. “It appears that the new predator is the increased development and other human activity that has picked up pace over the past several decades. “Mule deer and pronghorn are now experiencing 40-acre spacing of gas drilling pads and thousands of miles of roads and pipelines. Too often, decisions have been made on individual projects while the impacts are occurring on a much broader scale.” Torbit said he fears mule deer and pronghorn populations may follow the steady decline of greater sage grouse that has been widely documented by wildlife researchers. “Forty years ago a hunter could see hundreds of sage grouse in a single day,” Torbit recalled. “But due to landscape-wide factors, the sage grouse population has suffered a slow, inexorable decline and so has sage grouse hunting. “As a Westerner, biologist and hunter, I don’t want to see that same decline occur in our mule deer and pronghorn,” Torbit said. NWF biologists have met with BLM officials and the Colorado Division of Wildlife and the Wyoming Department of Game and Fish to present and discuss the new analysis of deer and pronghorn herds. A series of public meetings is scheduled in communities within the study area in Wyoming and Colorado. “Ultimately, it will be up to all of who value our wildlife herds to urge federal and state agencies to make decisions that will protect our wildlife resource,” Torbit said. “The future of our hunting heritage and the billions of dollars wildlife brings to the region’s economy are at stake.”

Deer, pronghorn numbers decline in Colorado, Wyoming as demands on public lands rise