Anger in Japan over withheld radiation forecasts

By NORIMITSU ONISHI and MARTIN FACKLER

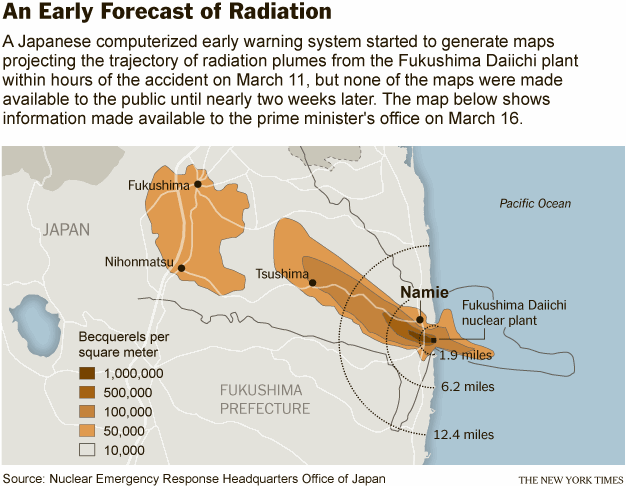

8 August 2011 FUKUSHIMA, Japan — The day after a giant tsunami set off the continuing disaster at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant, thousands of residents at the nearby town of Namie gathered to evacuate. Given no guidance from Tokyo, town officials led the residents north, believing that winter winds would be blowing south and carrying away any radioactive emissions. For three nights, while hydrogen explosions at four of the reactors spewed radiation into the air, they stayed in a district called Tsushima where the children played outside and some parents used water from a mountain stream to prepare rice. The winds, in fact, had been blowing directly toward Tsushima — and town officials would learn two months later that a government computer system designed to predict the spread of radioactive releases had been showing just that. But the forecasts were left unpublicized by bureaucrats in Tokyo, operating in a culture that sought to avoid responsibility and, above all, criticism. Japan’s political leaders at first did not know about the system and later played down the data, apparently fearful of having to significantly enlarge the evacuation zone — and acknowledge the accident’s severity.

“From the 12th to the 15th we were in a location with one of the highest levels of radiation,” said Tamotsu Baba, the mayor of Namie, which is about five miles from the nuclear plant. He and thousands from Namie now live in temporary housing in another town, Nihonmatsu. “We are extremely worried about internal exposure to radiation.” The withholding of information, he said, was akin to “murder.” In interviews and public statements, some current and former government officials have admitted that Japanese authorities engaged in a pattern of withholding damaging information and denying facts of the nuclear disaster — in order, some of them said, to limit the size of costly and disruptive evacuations in land-scarce Japan and to avoid public questioning of the politically powerful nuclear industry. As the nuclear plant continues to release radiation, some of which has slipped into the nation’s food supply, public anger is growing at what many here see as an official campaign to play down the scope of the accident and the potential health risks. Seiki Soramoto, a lawmaker and former nuclear engineer to whom Prime Minister Naoto Kan turned for advice during the crisis, blamed the government for withholding forecasts from the computer system, known as the System for Prediction of Environmental Emergency Dose Information, or Speedi. “In the end, it was the prime minister’s office that hid the Speedi data,” he said. “Because they didn’t have the knowledge to know what the data meant, and thus they did not know what to say to the public, they thought only of their own safety, and decided it was easier just not to announce it.” […] The computer forecasts were among many pieces of information the authorities initially withheld from the public. […]