The oceans are emptying fast

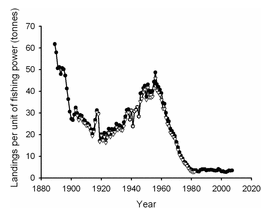

It was a shameful par for a very long course when European, Middle Eastern and North African governments met in Rome this month to decide how to save the fast-vanishing fisheries in their common sea. You’d think there would have been a sense of the need for urgent action at the annual meeting of the cumbersomely named General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean. After all, scientists had warned that 22 of the sea’s 23 stocks of bottom-living fish – including hake, mullet and red shrimp – are over-exploited, and called for drastic catch reductions in fishing. But even though the commission’s raison d’être is to “promote the development, conservation, rational management and best utilisation” of fish and other “living marine resources”, the meeting broke up last week without having adopted a single measure to address the decline. This was typical of the way governments have approached the ravaging of the seas, where we still catch what we can without, like farmers, taking care to maintaining and increasing the stock. And few measures have been more disastrous than the EU’s Common Fisheries Policy, whose meetings, former agriculture and fisheries minister William Waldegrave once told me, reminded him of “Buffalo Bill and Wyatt Earp arguing over who should shoot the last buffalo”. There are signs, even in Brussels, that attitudes are beginning to change – something I plan to explore at the Telegraph Hay Festival on Thursday, while chairing a debate, which includes fisheries minister Richard Benyon, on “fighting for a sensible fish future”. If so, it’s about time. For while geologists and economists are still arguing about when “peak oil” will hit us, we have long left “peak fish” in our wake. After growing almost fivefold since 1950 – twice the rate of population growth – the wild harvest from the seas peaked at some 93 million tons in 1997, and has been declining since; the total catch has only continued to grow thanks to increasingly widespread fish-farming. At least three quarters of the world’s fish stocks are being exploited at, or well beyond, the limit at which they can be sustained. And Europe’s waters are even more denuded, with 87 per cent of its stocks overfished. …