Fresh tales of chaos emerge from early in Fukushima nuclear crisis

By YUKA HAYASHI And PHRED DVORAK

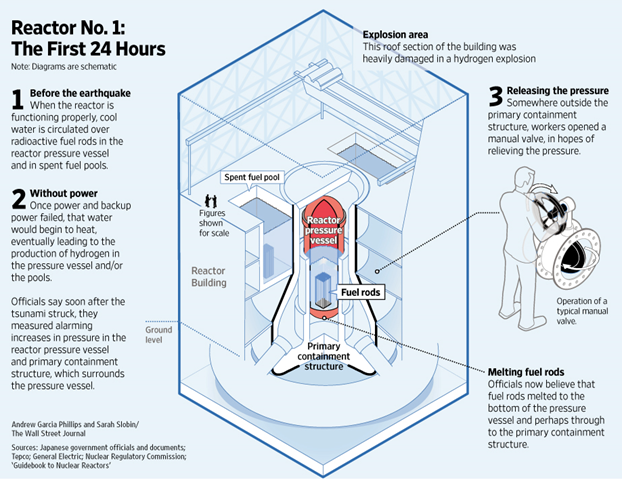

18 May 2011 FUKUSHIMA PREFECTURE, Japan—The Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant deteriorated in the crucial first 24 hours far more rapidly than previously understood, a Wall Street Journal reconstruction of the disaster shows. So helpless were the plant’s engineers that, as dusk fell after Japan’s devastating March 11 quake and tsunami, they were forced to scavenge flashlights from nearby homes. They pulled batteries from cars not washed away by the tsunami in a desperate effort to revive reactor gauges that weren’t working properly. The plant’s complete power loss contributed to a failure of relief vents on a dangerously overheating reactor, forcing workers to open valves by hand. And in a significant miscalculation: At first, engineers weren’t aware that the plant’s emergency batteries were barely working, the investigation found—giving them a false impression that they had more time to make repairs. As a result, nuclear fuel began melting down hours earlier than previously assumed. This week Tokyo Electric Power Co., or Tepco, confirmed that one of the plant’s six reactors suffered a substantial meltdown early in Day 1. Late Monday in Japan, Tepco released more than 2,000 pages of documents, dubbed reactor “diaries,” which also provide new glimpses of the early hours. Soon after the quake, but before the tsunami struck, workers at one reactor actually shut down valves in a backup cooling system—one that, critically, didn’t rely on electrical power to keep functioning—thinking it wasn’t essential. That decision likely contributed to the rapid meltdown of nuclear fuel, experts say. The Journal’s reconstruction is based on examination of Tepco and government documents, along with dozens of interviews with administration officials, corporate executives, lawmakers and regulators. It uncovered new details on how Tepco executives delayed for seven hours before formally deciding to vent a dangerous pressure buildup in one reactor, despite an unusual face-to-face clash between Japanese Prime Minister Naoto Kan and Tepco top brass.

Tepco executives have acknowledged they weren’t aware for hours of the severity of the crisis. By the time Tepco decided to vent its reactor, radiation levels were so high that the man who volunteered to hand-crank the relief valve open was exposed, in a few minutes, to 100 times the radiation an average person gets in a year.

The government itself, despite Mr. Kan’s hands-on involvement, failed to come up with a unified early response of its own. Not only were officials tripped up by overly optimistic assessments of the situation, but their own emergency-response building was without electricity and phones. “There was a lack of unity,” said Goshi Hosono, the cabinet official overseeing the Fukushima disaster.

When a magnitude-9 quake struck at 2:46 p.m. on March 11, many of Fukushima Daiichi’s managers were in a conference room at the plant for a meeting with regulators. They were just wrapping up when the ground shook, says Kazuma Yokota of the Nuclear and Industrial Safety Agency, or NISA, Japan’s nuclear regulator. Files toppled over. Walls and the ceiling cracked, sprinkling a fine, white dust. The electricity died. Mr. Yokota, a thin man with a quick, nervous laugh, recalls someone saying: “Wow, that was bad.” But the emergency appeared under control. Fukushima Daiichi’s three active reactors went into automatic shutdown, called a “scram.” And the backup diesel generators kicked in, powering emergency lights and a cacophony of alarms. Then, almost exactly one hour later, a tsunami roughly 50 feet high struck, killing the emergency generators. At 3:37 p.m., Teruaki Kobayashi, a Tepco nuclear-facilities chief in the company’s Tokyo war room, remembers Fukushima Daiichi calling in a “station blackout.” One of Japan’s largest nuclear plants had just gone dark. “Why would this be happening?” Mr. Kobayashi recalls thinking. A full blackout is something only the worst-case disaster protocols envision. His next thought was that the plant still had an eight-hour window to restore power before things really turned bad. That’s how long the plant’s backup batteries, its final line of defense, were supposed to last, cooling the reactor fuel rods and powering key instruments. Tepco engineers now believe the tsunami knocked out most, if not all, of the batteries, according to documents from Tepco on Monday. But they didn’t know that then. They thought the batteries were still working, giving them the eight-hour cushion. …