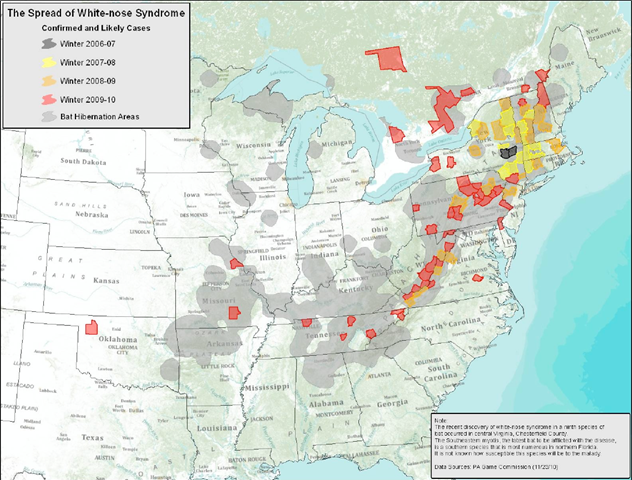

Graph of the Day: The Spread of White-nose Syndrome Across North America, 2006-2010

Contact: Mollie Matteson, Conservation Advocate

Center for Biological Diversity, Northeast Field Office

PO Box 188

Richmond, Vermont 05477

802-434-2388

mmatteson@biologicaldiversity.org In the span of just four winters, a deadly new disease called white-nose syndrome (WNS) that devastates bat populations has spread rapidly across the country from east to west. The bat illness was first documented in a cave in upstate New York in 2006, and as of spring 2010, the whitenose pathogen had been reported as far west as western Oklahoma. In affected bat colonies, mortality rates have reached as high as 100 percent, virtually emptying caves once harboring tens of thousands of bats and leaving cave floors littered with the innumerable small bones of the dead. At least six bat species are known to be susceptible, and the fungus associated with the disease has been found on another three species. Two federally listed endangered bat species are among those affected thus far. Scientists and conservationists are gravely concerned that if current trends continue, one or more bat species could become extinct in the next couple of decades or sooner. Biologists believe WNS is transferred primarily bat to bat, and from bat to cave or mine, where hibernating bats congregate. However, there is strong evidence that the WNS pathogen — a newly described fungus — was transported to North America via human transmission. The fungus has been identified in Europe, but does not appear to sicken bats there. It is thus believed that the fungus, Geomyces destructans, was introduced to North America from Europe by an unwitting caver. Fungal material appears to be easily transferred between caves via clothing, boots and other gear, suggesting that human transport may play a significant role in long-distance transmission of the disease. Given this risk, it is critically important that human access to caves be restricted, particularly in areas where the disease is not currently known, including large areas of the western United States. Decontamination measures, while helpful, are quite painstaking and even if carried out well are not a complete guarantee that fungal material will be removed from contaminated clothing and gear. As the white-nose fungus has been consistently found in soils of WNS-infected caves, “wild” or off-trail caving (as opposed to guided tours on developed paths) tends to pose the greatest risk of fungal transport, as boots and other gear can become quite muddy. To address the critical need for cave closures, the Center for Biological Diversity filed an Administrative Procedure Act petition in January 2010 calling for the administrative closure of all bat caves and abandoned mines on federal lands in the lower 48 states. One year later, we have surveyed all the major federal public land agencies (U.S. Forest Service, National Park Service, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and Bureau of Land Management) to determine the extent of WNS-related cave and mine closures across the country and found that although caves have been closed across much of the eastern United States, many areas in the West remain open.

Bats, White-nose Syndrome and Federal Cane and Mine Closures [pdf]