Rising seas threaten North Carolina coast

By Bruce Henderson, Charlotte Observer

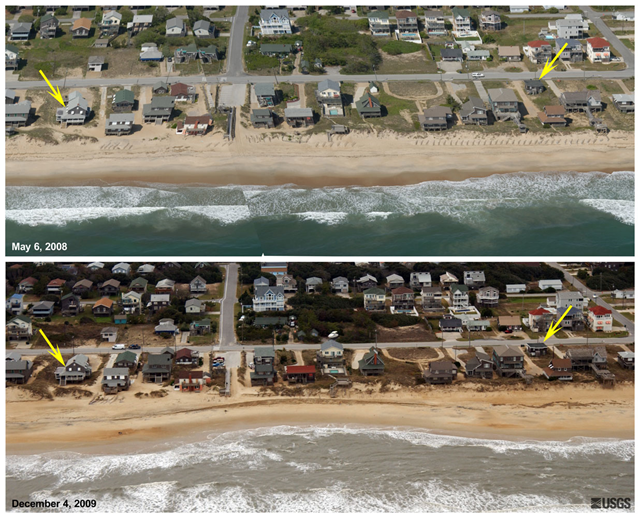

January 16, 2011 MANNS HARBOR, N.C. — The sea that sculpted North Carolina’s coast, from its arc of barrier islands to the vast, nurturing sounds, is reshaping it once again. Water is rising three times faster on the N.C. coast than it did a century ago as warming oceans expand and land ice melts, recent research has found. It’s the beginning of what a N.C. science panel expects will be a 1-meter increase by 2100. Rising sea level is the clearest signal of climate change in North Carolina. Few places in the United States stand to be more transformed. About 2,000 square miles of our low, flat coast, an area nearly four times the size of Mecklenburg County, is 1 meter (about 39 inches) or less above water. At risk are more than 30,500 homes and other buildings, including some of the state’s most expensive real estate. Economists say $6.9 billion in property, in just the four counties they studied, will be at risk from rising seas by late this century. Climate models predict intensifying storms that could add billions of dollars more in losses to tourism, farming and other businesses. While polls show growing public skepticism of global warming, the people paid to worry about the future – engineers, planners, insurance companies – are already bracing for a wetter world. “Sea-level rise is happening now. This is not a projection of something that will happen in the future if climate continues to change,” said geologist Rob Young of Western Carolina University, who studies developed shorelines. … Sea-level rise magnifies two other powerful forces – erosion that gouges the coastline and the pounding of nor’easters and tropical storms. Storms, Young said, are “the hammer” of rising seas. As storm surges pound ashore on a higher base of water, their damage multiplies. The Outer Banks, some scientists predict, could disintegrate into a string of high spots – Avon, Buxton, Ocracoke – reachable only by boat. If storms punch new inlets through the islands, the brackish sounds and wetlands that serve as vital nurseries for Atlantic coast seafood species would turn into open saltwater. Predatory fish would pour into previously protected waters. Marshes would migrate inland or drown. Dead bald cypress trees already rim the Albemarle-Pamlico Peninsula, graying in the encroaching salty water that engulfed and killed them. Much of the peninsula, which juts toward the northern Banks and is one the state’s richest wildlife sanctuaries, could be underwater by century’s end. Human habitats will be forced into momentous decisions – fortify or flee. A row of beach houses in the old resort town of Nags Head is collapsing into the surf now as the town plans a $36 million project to pump fresh sand onto its eroding strand this spring. Down the coast, in North Topsail Beach, property owners are waffling on helping to pay for a $10 million nourishment project. … It seems implausible that an almost imperceptible rise in the sea – about the thickness of two nickels a year – could cause such havoc. But it took only an 8-inch global rise to threaten the iconic Cape Hatteras Lighthouse, which was 1,500 feet from the Atlantic when it was built in 1870. By 1999, when hydraulic jacks gingerly nudged the striped brick tower inland, waves crashed at its foundation. … Coastal geologists who reconstructed sea-level changes on the northeastern N.C. coast say levels were stable for 3,000 years. The sea began rising in the 19th century. The rate of climb doubled again in the 20th century, with a further quickening in the past 30 years. Alonzo Leary gauges the changes over the 74-year span of his life. Raised near Albemarle Sound in a farming community called Alligator, he left as a young man to find work. He returned 20 years later to find old swimming holes flooded and the sound closer to road level. “I notice that the swamps stay full of water most of the time,” Leary said. Scientists envision more acceleration this century. Some say seas could rise to as much as 6 feet above current levels by 2100 if large ice masses melt in Greenland and Antarctica. … When state transportation engineer Ted Devens and his colleagues recently designed a 28-mile widening of U.S. 64 across the Albemarle-Pamlico Peninsula, they raised the roadbed by a foot to allow for rising seas. It was a first for an N.C. Department of Transportation road project. “What we’re trying to do is get away from the hype and just look at the data,” said Devens, who works in project development and environmental analysis. “Our data tells us sea level is rising. “What do you plan for? That’s been the big question.” … Rob Young, the coastal geologist, credits the state’s planning efforts. But if the state were serious about adapting to rising seas, he says, it would be smarter in responding to the storms that already hammer the coast. Beach communities shredded by hurricanes are typically built back, sometimes repeatedly. Taxpayers subsidize federal flood insurance, roads and bridges. If seas rise by 1 meter, Young said, engineers could fix the holes storms would blow through the rim of barrier islands, as long as the state can afford repairs. The problem of the future is that Charleston, Miami and other East coast cities also would be struggling to keep their heads above water. “If we have to fix Manhattan,” he said, “Hatteras is not going to compete for money real well.”