Globalization burdens future generations with biological invasions, study finds

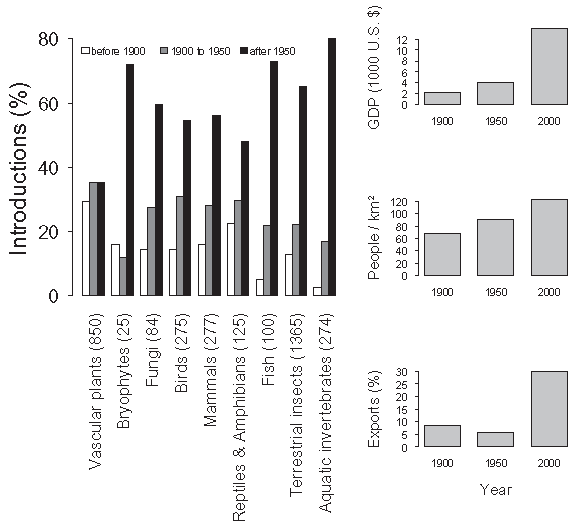

ScienceDaily (Dec. 20, 2010) — The consequences of the current high levels of socio-economic activity on the extent of biological invasions will probably not be completely realized until decades into the future, according to new research. A new study on biological invasions based on extensive data of alien species from 10 taxonomic groups and 28 European countries has shown that patterns of established alien species richness are more related to historical levels of socio-economic drivers than to contemporary ones. An international group of 16 researchers reports the new finding in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). The publication resulted from the three-year project DAISIE (Delivering Alien Invasive Inventory for Europe, www.europe-aliens.org), funded by European Union within its 6th Framework Programme. Recent research has demonstrated that economic activities are among the most important determinants of biological invasions, fostering discussions about appropriate political strategies to prevent unintended introductions, e.g. in terms of trade regulations. Yet the frequent delay between first introduction of a species in a new territory and its establishment and spread suggest that invasions triggered by current economic behavior will possibly take a long time to become fully realized, causing what the researchers call an “invasion debt.” Taking an historical approach, this new study provides an explicit test of this phenomenon. The researchers selected three predictors of socio-economic activity linked to invasions — human population density, per capita GDP, and, as a measure of trade intensity (i.e., openness of an economy) the share of exports in GDP, and demonstrated that current alien species richness is better explained by socio-economic data from 1900 than from 2000. The strength of the historical signal varies among taxonomic groups with those possessing good capabilities for dispersal (birds, insects) more strongly associated with recent levels of socioeconomic drivers. Nevertheless, the results suggest a considerable historical legacy for the majority of the species groups analyzed. “The broad taxonomic and geographic coverage indicates that such an ‘invasion debt’ is a widespread phenomenon,” says Franz Essl from the Austrian Environment Agency. “This inertia is worrying as it implies that current, increased levels of socio-economic activity will probably lead to continuously rising levels of invasion during the upcoming decades, even if new introductions could be successfully reduced,” explains Stefan Dullinger from the University of Vienna. Therefore, the scientists write “…the seeds of future invasion problems have already been sown” and they expect the problem of invasive species to become worse in the next few decades. They say that efforts to control invasive species should be expanded with a special focus on not only those species currently most harmful, but also on early warning and rapid response for species already in the territory that are likely to pose the greatest future threat.

Globalization burdens future generations with biological invasions, study finds