Scientists wary of BP oil spill’s long-term effects on species

By Mark Schleifstein, The Times-Picayune

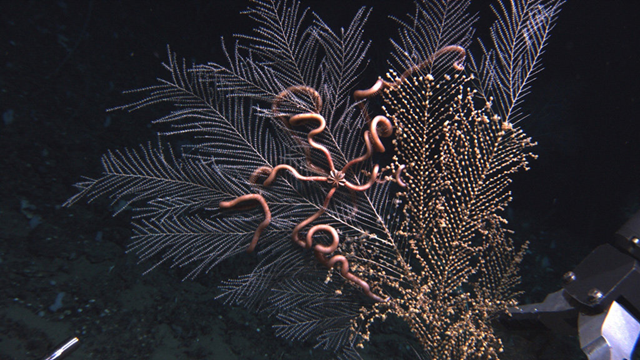

Wednesday, November 10, 2010, 8:56 PM Federal officials planning the recovery from the effects of the BP Macondo oil spill should remain on guard for signs of the collapse of fish or wildlife species in and around the Gulf of Mexico in the years to come, say more than 40 scientists gathered in Sarasota, Fla., to discuss long-term scientific responses to the spill. At the top of their recommendations is the creation of a unified research and monitoring effort to detect the first signs of trouble with Gulf species and provide that information to management agencies to head off disastrous effects, said marine biologist Michael Crosby, senior vice president for research at Mote Marine Laboratory. “Right now there is no agency that pulls together and coordinates all the information we need about the Gulf,” Crosby said Wednesday at the conclusion of the two-day symposium. “Scientists at different institutions might be collecting different pieces of data — but if we don’t put those together, we could miss the big picture until populations crash.” The gathering at the private Mote Marine Laboratory was co-sponsored by the National Wildlife Foundation and the College of Marine Sciences at the University of South Florida. Attending were representatives of regional fishery management councils; local, state and federal resource management agencies; fishing and other industries; academic and independent research institutions; and environmental groups. The participants focused on the potential for “trophic cascades,” changes affecting a single or multiple species in the Gulf food chain that could cause stress or declines in populations of organisms at other stages in the food chain. Such a cascade is believed to have caused the collapse of the Pacific herring fishery in Alaskan waters in 1993, four years after the Exxon-Valdez oil spill. “We’re seeing clear evidence of impacts as recently as the end of the past week, with vivid photographs of deepwater coral impacted by what was referred to as a brown substance,” Crosby said during a Tuesday news conference, referring to the findings of scientists at locations seven miles away from the BP Macondo well in coral fields nearly a mile beneath the ocean’s surface. “They have seen oil in the gills of shrimp,” said William Hogarth, dean of South Florida’s marine sciences college and former assistant administrator for fisheries with the National Marine Fisheries Service, referring to varied reports of scientists along the Gulf coast. “There may not be an immediate effect on species right now, but we could be seeing such an effect in a year, three years, five years from now.” Indeed, some scientists at the conference expressed concern that the effects of oil on endangered shark species or on their food sources could be the “tipping point” that pushes them into extinction, Crosby said. Other species that could face long-term changes include shrimp, menhaden, blue crabs, various types of plankton, coral reefs, sargassum algae, seabirds, tuna, dolphins, sea turtles, and mackerel, tarpon and other key sport fish. …

Scientists wary of BP oil spill’s long-term effects on species