Hatch-22: The problem with the Pacific salmon resurgence

The number of salmon in the Pacific Ocean is twice what it was 50 years ago. But there is a downside to this bounty, as growing numbers of hatchery-produced salmon are flooding the Pacific and making it hard for threatened wild salmon species to find enough food to survive.

By Bruce Barcott

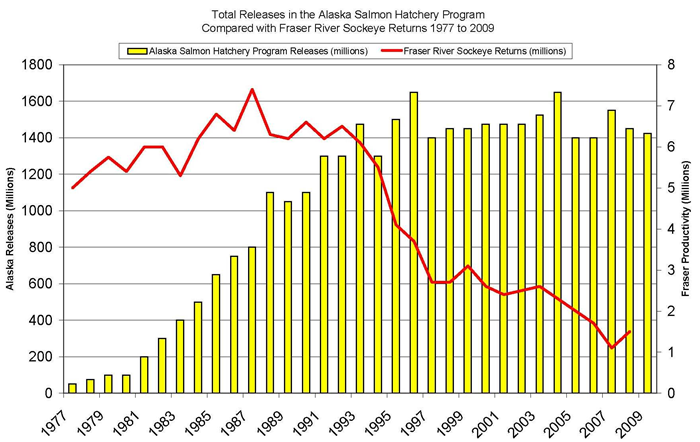

01 Nov 2010 In the American Northwest, the struggle to save endangered runs of salmon is one of the epic crusades of the contemporary conservation movement. Seventeen strains of Pacific salmon are currently listed as threatened or endangered. Two more are labeled “species of concern,” meaning they are close to jumping onto the list. So what are we to make of this: A recent study, “Magnitude and Trends in Abundance of Hatchery and Wild Pink Salmon, Chum Salmon, and Sockeye Salmon in the North Pacific Ocean”, published in the journal Marine and Coastal Fisheries, found that the north Pacific Ocean may be nearing the limit of its salmon-carrying capacity. The North Pacific is becoming “overcrowded with salmon,” according to Randall Peterman, one of the study’s authors and holder of the Canada Research Chair in Fisheries Risk Assessment and Management at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver, B.C. He and his co-author, Seattle-based fisheries biologist Greg Ruggerone, recently set out to compile the most complete set of data on Pacific salmon abundance. What they found is that today’s total Pacific salmon population is twice what it was 50 years ago. “We’re seeing more total salmon now than we’ve ever seen before,” says Peterman. A surprising number of those fish — more than one in five — originate in hatcheries. And that has created its own set of problems. Masses of hatchery-bred salmon are gobbling up smaller fish, krill, and other prey, reducing food supplies in the North Pacific for endangered wild runs and hampering their recovery. In addition, hatchery fish, which come from limited brood stock with less diverse DNA, aren’t as genetically fit as wild salmon to support the long-term survival of the species. How can numerous Pacific salmon runs be on the verge of extinction while total salmon numbers are straining the limits of the ocean’s capacity to support them?

According to the researchers, the abundance of some salmon species has been caused by a resurgence in wild salmon populations due to productive ocean conditions, as well as to the ever-increasing production of hatchery fish. But the problem is, the resurgence of wild populations hasn’t been universal. Five species of salmon exist in the Pacific: Pink, chum, sockeye, coho, and Chinook. (The Atlantic Ocean has only one species, the Atlantic salmon.) Over the past quarter-century, pink salmon populations from around the Pacific Rim have doubled, thanks, in part, to hatchery production. Other runs, such as Upper Columbia River Chinook and Snake River sockeye, limp along in alarmingly low numbers. The triumph of industrial salmon hatcheries is written in the numbers. Between 1970 and the late 1980s, the U.S., Canada, and their Pacific Rim neighbors ramped up their hatchery programs and pumped out vast numbers of young salmon. In 1970, hatcheries released around 500 million young salmon into the Pacific. By 2008 (the last year for which data is available), that figure had jumped ten-fold, to 5 billion. Most of those hatchery fish — about 90 percent — were pink or chum, the most common of the five species of Pacific salmon. Japanese hatcheries pump so many chum salmon into the Pacific that hatchery chum have outnumbered wild chum since the mid-1980s. One-third of Alaska’s 2010 statewide salmon harvest originated from five hatcheries in the Prince William Sound/Copper River region. …