Peak water: Conceptual and practical limits to freshwater withdrawal and use

Media Contact: Nancy Ross, Pacific Institute, nross@pacinst.org

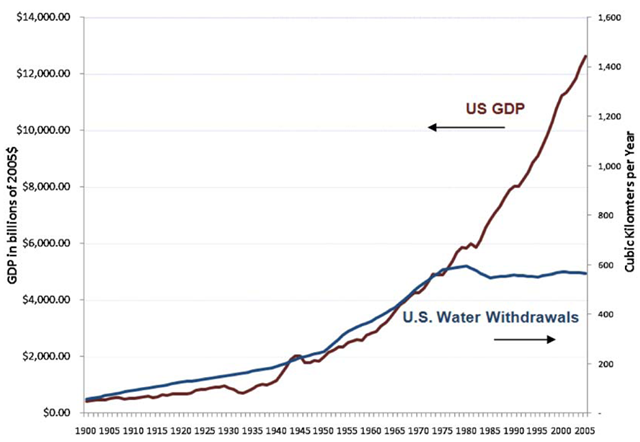

May 24, 2010 A new journal article from the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) highlights new “peak water” limits to global and regional freshwater availability and use. The May 24, 2010 early edition of the journal includes the new article “Peak Water Limits to Freshwater Withdrawal and Use” [pdf] by authors Dr. Peter Gleick, president of the Pacific Institute, and Meena Palaniappan, director of the Institute’s International Water and Communities Initiative, and brings sharp focus to understanding the world’s water issues in new terms of “peak renewable water,” “peak nonrenewable water,” and “peak ecological water.” Are we running out of water? No, Gleick and Palaniappan argue we will not “run out” of water on earth – but we are very close to using much of the renewable supply and in some regions we are well past the point of peak ecological water – where the environmental damage of human use of water exceeds the benefits of that water use. The specter of “peak oil” – a peaking and then decline in oil production – has long been predicted and debated. Gleick and Palaniappan assess “peak water” as way to help water managers and policymakers, and all of us as water users, understand and manage different water systems more effectively and sustainably. They describe peak water in three ways:

- Peak renewable water: where flow constraints limit total water availability over time.

- Peak nonrenewable water: where production rates substantially exceed natural recharge rates or where overpumping or contamination leads to a peak production followed by a decline (similar to peak oil curves).

- Peak ecological water: the point beyond which the total costs of ecological disruptions and damages exceed the total value provided by human use of that water.

These concepts can help shift the way freshwater resources are managed toward more productive, equitable, efficient, and sustainable use. One of the most important outcomes of the concept of peak water is that it signals the end of cheap and easy access to water. This recognition of the value of water can drive us to an important and needed paradigm shift in the way water is managed and priced — toward a soft path for water, a strategy that improves the productivity, equity, and efficiency of water use.

PEAK WATER: New Paper Identifies Limits to Global and Regional Freshwater Availability for Human Use