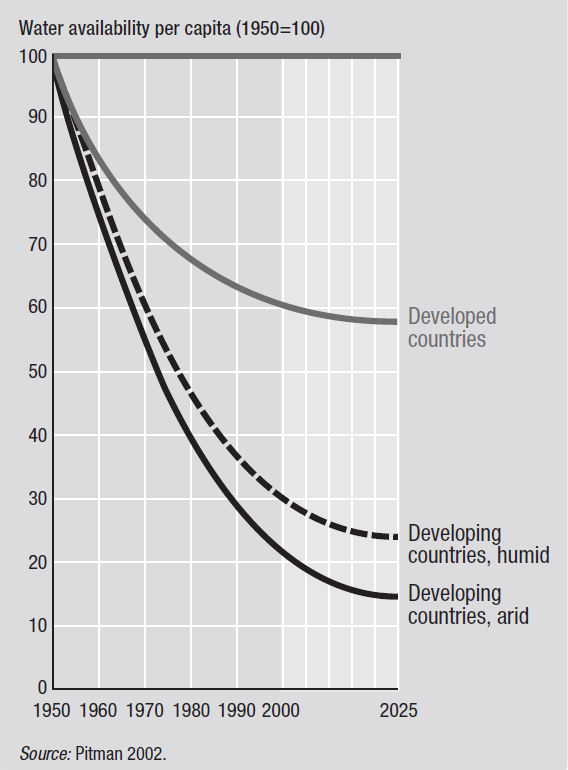

Graph of the Day: Global Water Availability Per Capita, 1950-2000

Measured on conventional indicators, water stress is increasing. Today, about 700 million people in 43 countries live below the water-stress threshold of 1,700 cubic metres per person—an admittedly arbitrary dividing line. By 2025 that figure will reach 3 billion, as water stress intensifies in China, India and Sub-Saharan Africa. Based on national averages, the projection understates the current problem. The 538 million people in northern China already live in an intensely water-stressed region. Globally, some 1.4 billion people live in river basin areas where water use exceeds sustainable levels. Water stress is reflected in ecological stress. River systems that no longer reach the sea, shrinking lakes and sinking groundwater tables are among the most noticeable symptoms of water overuse. The decline of river systems—from the Colorado River in the United States to the Yellow River in China—is a highly visible product of overuse. Less visible, but no less detrimental to human development, is rapid depletion of groundwater in South Asia. In parts of India groundwater tables are falling by more than 1 metre a year, jeopardizing future agricultural production. These are real symptoms of scarcity, but the scarcity has been induced by policy failures. When it comes to water management, the world has been indulging in an activity analogous to a reckless and unsustainable credit-financed spending spree. Put simply, countries have been using far more water than they have, as defined by the rate of replenishment. The result: a large water-based ecological debt that will be transferred to future generations. This debt raises important questions about national accounting systems that fail to measure the depletion of scarce and precious natural capital—and it raises important questions about cross-generational equity. Underpricing (or zero pricing in some cases) has sustained overuse: if markets delivered Porsche cars at give-away prices, they too would be in short supply. Future water-use scenarios raise cause for serious concern. For almost a century water use has been growing almost twice as fast as population. That trend will continue. Irrigated agriculture will remain the largest user of water—it currently accounts for more than 80% of use in developing countries. But the demands of industry and urban users are growing rapidly. Over the period to 2050 the world’s water will have to support the agricultural systems that will feed and create livelihoods for an additional 2.7 billion people. Meanwhile, industry, rather than agriculture, will account for most of the projected increase in water use to 2025.

Beyond scarcity: Power, poverty and the global water crisis [pdf]