Invasive mollusk disrupting base of Lake Michigan ecosystem — ‘We have a system that’s crashing’

By Marcia Goodrich

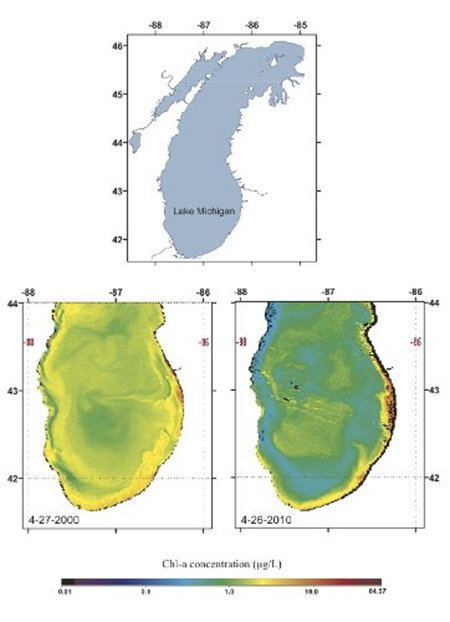

September 7, 2010 12:23 PM September 2, 2010 — Something has been eating Charlie Kerfoot’s doughnut, and all fingers point to a European mollusk about the size of a fat lima bean. No one knew about the doughnut in southern Lake Michigan, much less the mollusk, until Michigan Technological University biologist W. Charles Kerfoot and his research team first saw it in 1998. That’s because scientists have always been wary of launching their research vessels on any of the shipwreck-studded Great Lakes in winter. But NASA’s new Sea-viewing Wide Field-of-view Sensor (SeaWiFS) Project was giving scientists a safer way to look at the lakes in bad weather. SeaWiFS satellite data showed Kerfoot’s team a roughly circular river of phytoplankton—algae and other tiny plants—that was drifting counterclockwise around the southern end of Lake Michigan, creating a doughnut. The group determined that the doughnut was formed when big winter storms kicked up sediments along the southeastern shore of the lake. There, Michigan’s biggest rivers drain a watershed rich in phosphorus and other nutrients from cities and farms. Those nutrients settle in the lake’s sediments until storms stir them up. Then, suspended in the water column, they begin circulating in a slow-moving gyre that flows from Grand Haven in the north to Chicago in the south. That gyre creates a Thanksgiving feast for phytoplankton. “We saw that with each storm, you get a ring, and it can persist for weeks or even months,” says Kerfoot. “We were floating in the clouds, saying ‘Hey, we discovered a new phenomenon,’” he remembers. Samples of lake water taken from research vessels verified the satellite data. Plus, they found that zooplankton, the tiny animals that feed on phytoplankton, were much more abundant in the doughnut. For them, the seasonal bloom was an all-you-can-eat salad bar, an important part of their strategy to survive winter. Those zooplankton were eaten in turn by small fish, which were eaten by large fish, which fueled an angling paradise productive enough to merit the nickname Lake Fishigan. Then, almost as soon as it was discovered, the doughnut started to disappear. “Since 2001, the chlorophyll has been nibbled away on the edges, right where the quaggas are,” says Kerfoot. … Using SeaWiFS, graduate student Foad Yousef has plotted a 75 percent decline in chorophyll a, a measure of phytoplankton abundance, from 2001 to 2008. “You are seeing a displacement of productivity from the water column to the benthic layer,” Kerfoot says. “It’s fascinating.” … That means that all the energy in the phytoplankton, which once fed fish, is being sucked down to the bottom of the lake by quaggas, who then eject it in the form of pseudo feces—mussel poop. That can stimulate the growth of Cladophora algae, which die, decompose and remove all the oxygen from the surrounding water, to ill effect. “When things go anaerobic, that kills off everything, including the quaggas, and creates conditions for botulism. We’ve had massive kills of fish-eating birds—loons, mergansers,” says Kerfoot. “Isn’t that bizarre? Who would have predicted that?” … “A high percent of the fish biomass could be lost in the next couple years,” Kerfoot says. NOAA scientists have already documented declines in several species. “We have a system that’s crashing.” …

Death of the “Doughnut”: How Quaggas Are Casting a Pall on the Lake Michigan Fishery