Crop-killing fungus spreads out of Africa toward the world’s bread baskets

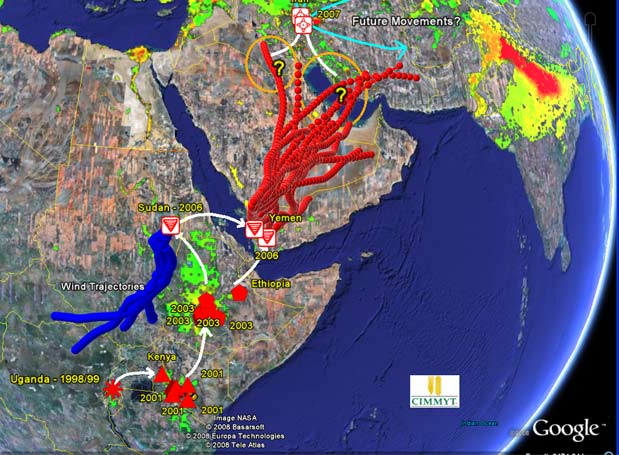

Jul 1st 2010 IT IS sometimes called the “polio of agriculture”: a terrifying but almost forgotten disease. Wheat rust is not just back after a 50-year absence, but spreading in new and scary forms. In some ways it is worse than child-crippling polio, still lingering in parts of Nigeria. Wheat rust has spread silently and speedily by 5,000 miles in a decade. It is now camped at the gates of one of the world’s breadbaskets, Punjab. In June scientists announced the discovery of two new strains in South Africa, the most important food producer yet infected. Wheat rust is a fungal infection. Its most devastating form (Puccinia graminis) attacks the plant’s stem, forming lethal, scaly red pustules. It has plagued crops for centuries. The Romans deified it, and believed that sacrificing dogs warded it off. It was the worst wheat disease of the first half of the 20th century, killing about a fifth of America’s harvest in periodic epidemics. Wheat rust once spurred the Green Revolution, the huge increase in crop yields that started in the 1940s. Now it could threaten those great gains. Norman Borlaug, the great American agronomist who died last year, conducted his original research into wheat rust. After ten years of painstaking crossbreeding, he isolated a gene, Sr31 (Sr for stem rust) that resisted P. graminis. By wonderful good fortune, Sr31 also boosted yields (and not only because plants were impervious to rust). Farmers everywhere adopted his seeds enthusiastically, saving millions of lives. So fast did his new varieties spread that by the 1970s, stem rust seemed to have been wiped out. But in 1998 William Wagoire, a pupil of Borlaug’s, was in south-western Uganda researching stripe rust, a less-deadly form of the disease that remains endemic there. While testing a new variety’s resistance, he was alarmed to find stems scarred not by the yellow streaks of stripe rust but the angry pustules of stem rust. At first neither he nor Borlaug’s International Maize and Wheat Improvement Centre (CIMMYT) in Mexico could believe their eyes: stem rust could not have survived all those years. The awful truth dawned only after a second opinion, by Zak Pretorius of the University of the Free State in South Africa: stem rust had not only lived on in a remote corner of Africa’s Great Lakes. It had evolved to overcome the previously unconquered Sr31. After decades without infection, most of the world’s wheat crop was defenceless. Wheat rusts spread as billions of spores in the wind. They usually move incrementally, from field to adjoining field, needing wet weather to thrive. But they can make larger leaps. They also mutate as they go. Rust, Borlaug once said, “never sleeps.” The new variant is called Ug99: Ug for its country of origin; 99 for the year it was confirmed. It soon spread to Kenya and Ethiopia. In 2006 it made a leap over the Red Sea into Yemen, where it appeared in a more deadly form. In 2007 it showed up in Iran, apparently blown from Yemen. In June scientists announced they had found four new mutations of rust (making seven in all) and Mr Pretorius confirmed its presence in a harmful form in South Africa. This could mark a final stage before disaster strikes. Rust’s appearance in South Africa means the disease has pushed deep into the southern hemisphere for the first time. Mr Pretorius worries that westerly winds might blow spores as far as Australia, which is one of the world’s top five wheat exporters. Iran borders Pakistan, which is among the top ten wheat producers and where roughly 100m people depend on the cereal to survive. David Hodson of the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation’s Wheat Rust Disease Global Programme thinks it is only a matter of time before Ug99 appears in Pakistan. …