China's wars, rebellions driven by climate: study

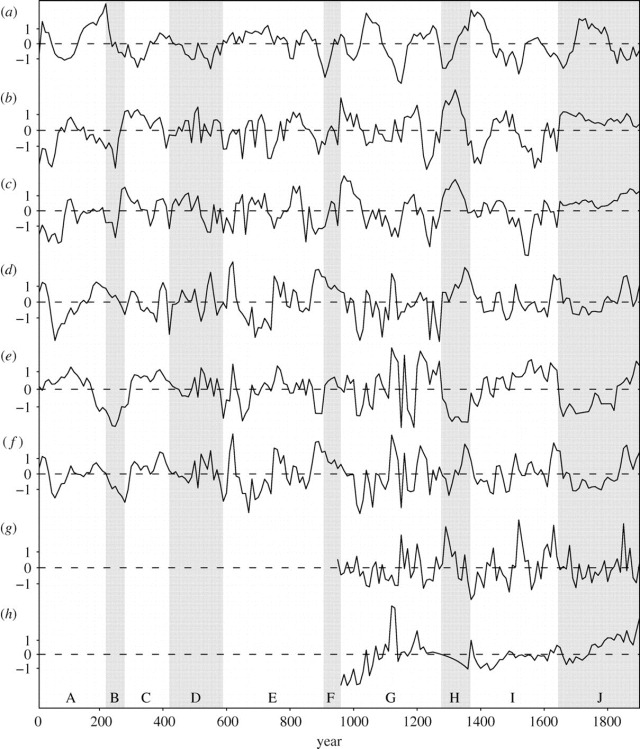

Decadal means of temperature of (a) the whole of China, (b) frequencies of droughts, (c) floods, (d) internal wars, (e) external aggression wars, (f) all wars, (g) locust plagues and (h) rice price in China during AD 10–1990. Dynastic periods are defined by following Chen (1939) as: A, Han (206 BC–AD 220); B, Three Kingdoms (AD 220–280); C, Jin (AD 280–420); D, Southern and Northern Dynasties (AD 420–589); E, Sui & Tang (AD 589–906); F, Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms (AD 907–959); G, Song (AD 960–1279); H, Yuan (AD 1276–1367); I, Ming (AD 1368–1643); J, Qing (AD 1644–1911).

By Staff Writers

Paris (AFP) July 14, 2010 Two millennia of foreign invasions and internal wars in China were driven more by cooling climate than by feudalism, class struggle or bad government, a bold study released Wednesday argued. Food shortages severe enough to spark civil turmoil or force hordes of starving nomads to swoop down from the Mongolian steppes were consistently linked to long periods of colder weather, the study found. In contrast, the Central Kingdom’s periods of stability and prosperity occurred during sustained warm spells, the researchers said. Theories that weather-related calamities such as drought, floods and locust plagues steered the unraveling or creation of Chinese dynasties are not new. But until now, no one had systematically scanned the long sweep of China’s tumultuous history to see exactly how climate and Chinese society might be intertwined. Chinese and European scientists led by Zhibin Zhang of the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing decided to compare two sets of data over 1,900 years. Digging into historical archives, they looked at the frequency of war, price hikes of rice, locust plagues, droughts and floods. For conflict, they distinguished between internal strife and external wars. At the same time, they reconstructed climate patterns over the period under review. “The collapses of the agricultural dynasties of the Han (25-220), Tang (618-907), Northern Song (960-1125), Southern Song (1127-1279) and Ming (1368-1644) are closely associated with low temperature or the rapid decline in temperature,” they conclude. A shortage of food would have weakened these dynasties, and pushed nomads in the north — even more vulnerable to dips in temperature — to invade their southern, Chinese-speaking neighbours, the authors argued. A drop of 2.0 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) in average annual air temperature can shorten the growing season for steppe grasses, which are critical for livestock, by up to 40 days. “When the climate worsens beyond what the available technology and economic system can compensate for, people are forced to move or starve,” they said. …

China’s wars, rebellions driven by climate: study