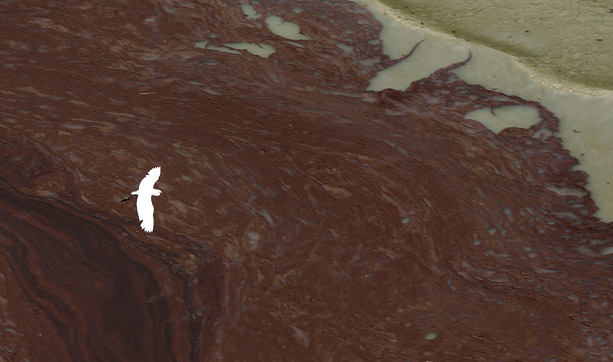

Oiled birds everywhere, but little rescue crews can do

Grand Isle, Louisiana (AFP) June 14, 2010 – Michael Seymour peers at the oiled pelican floating near an island of mangrove trees and winces in frustration because — once again — there’s absolutely nothing he can do to help. An amber sheen has stained the pelican’s white head and brown chest and wings. But the oil isn’t thick enough to keep it from flying away if Seymour approaches. “The only way to catch a bird in that condition is to chase it repeatedly until it gets tired,” says Seymour, an ornithologist with the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries. “We’re just going to be putting him under more stress than we need to.” Oiled birds aren’t hard to find some 54 days after an explosion on the BP-leased Deepwater Horizon drilling rig sparked the worst environmental catastrophe in US history. The problem is finding a bird that can be rescued without doing more harm than good, Seymour says. He’s seen eggs crushed by well-meaning amateurs who trampled through a pelican colony to capture a single oiled bird. Even stepping onto a rocky shore can send hundreds of panicked nesting birds into the skies, exposing their fledglings and eggs to the sweltering sun. Taking an oiled chick away from its parents means it may never learn the skills it needs to survive on its own. And capturing a lightly oiled bird still able to fly and feed itself could mean leaving its chicks or eggs untended. “It’s a tough decision to make, but sometimes we have to make hard decisions for the greater good of the birds,” Seymour says as he directs the boat captain to move on to another island and leave the oiled pelican behind. …