The dark side of nitrogen

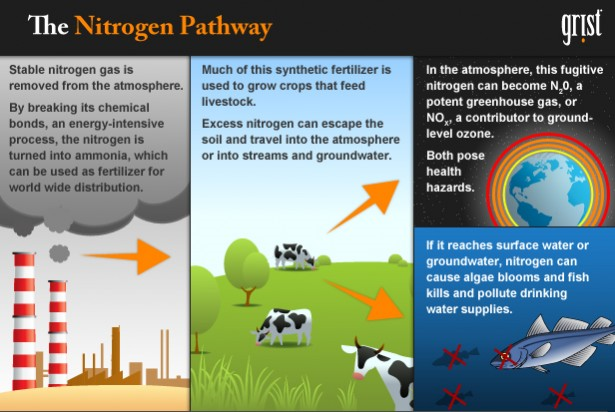

By Stephanie Ogburn, 4 Feb 2010 2:00 PM …To see nitrogen’s ill effects up close head to the mid-Atlantic coast and visit the Chesapeake Bay, the nation’s largest estuary. Once the site of a highly productive fishery and renowned for its oysters, crabs, and clams, today the bay is most famous for its ecological ruin. On Dec. 9, 2008, the Environmental Protection Agency’s restoration program for the Chesapeake Bay marked its 25th anniversary. Other than the passing of the years, there wasn’t much to celebrate. The Chesapeake Bay Program’s goal is rehabilitation of the vastly polluted estuary, yet its 2008 “Bay Barometer” assessment found that “despite small successes in certain parts of the ecosystem and specific geographic areas, the overall health of the Chesapeake Bay did not improve in 2008.” (The fight to save the Chesapeake continues; in 2009, President Obama ordered the federal EPA to lead the ongoing cleanup efforts, but groups involved are still arguing over the details.) A significant portion of the Chesapeake Bay pollution comes from agricultural operations whose nutrient-rich runoff—in the form of excess nitrogen and phosphorus—fills the Bay’s waters, leading to algal blooms, fish kills, habitat degradation, and bacteria proliferations that endanger human health. The nitrogen runoff comes from the synthetic fertilizer applied to farm fields, as well as the manure generated from the intensive chicken farming on the east bay. Of course, the nitrogen in that chicken manure—some 650 million pounds per year, according to The New York Times— can largely be traced to synthetic nitrogen; the chickens are merely recycling the synthetic fertilizer that was originally applied to feed crops. This type of reactive nutrient pollution is now so common that the dead zones, acidified lakes, and major habitat degradation it can cause are occurring with greater frequency, not just in the Chesapeake Bay, but in other parts of the United States and around the world. …