Few remain in Pennsylvania coal town as 1962 fire still burns

By MICHAEL RUBINKAM

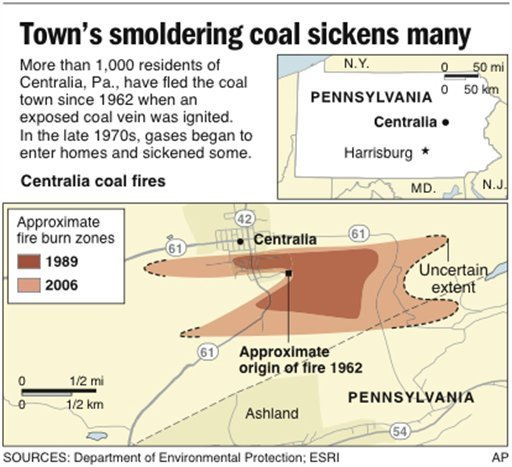

Associated Press Writer Standing before the wreckage of his bulldozed home, John Lokitis Jr. felt sick to his stomach, certain that a terrible mistake had been made. He’d fought for years to stay in the house. It was one of the few left standing in the moonscape of Centralia, a once-proud coal town whose population fled an underground mine fire that began in 1962 and continues to burn. But the state had ordered Lokitis to vacate, leaving the fourth-generation Centralian little choice but to say goodbye – to the house, and to what’s left of the town he loved. “I never had any desire to move,” said Lokitis, 39. “It was my home.”After years of delay, state officials are now trying to complete the demolition of Centralia, a borough in the mountains of northeastern Pennsylvania that all but ceased to exist in the 1980s after the mine fire spread beneath homes and businesses, threatening residents with poisonous gases and dangerous sinkholes. More than 1,000 people moved out, and 500 structures were razed under a $42 million federal relocation program. But dozens of holdouts, Lokitis included, refused to go – even after their houses were seized through eminent domain in the early 1990s. They said the fire posed little danger to their part of town, accused government officials and mining companies of a plot to grab the mineral rights and vowed to stay put. State and local officials had little stomach to oust the diehards, who squatted tax- and rent-free in houses they no longer owned. … In reality, Centralia is already a memory – an intact street grid with hardly anything on it. All the familiar places that define a town – churches, businesses, schools, homes – are long gone. A hand-lettered sign tacked to a tree near Womer’s home directs tourists to a rocky outcropping off the main street where opaque clouds of steam rise from the ground. … The fire began at the town dump and ignited an exposed coal vein. It could have been extinguished for thousands of dollars then, but a series of bureaucratic half-measures and a lack of funding allowed the fire to grow into a voracious monster – feeding on millions of tons of slow-burning anthracite coal in the abandoned network of mines beneath the town. At first, most Centralians ignored the fire. Some denied its existence, choosing to disregard the threat. That changed in the 1970s, when carbon monoxide began entering homes and sickening people. The beginning of the end came in 1981, when a cave-in sucked a 12-year-old boy into a hot, gaseous void, nearly killing him. The town divided into two warring camps, one in favor of relocation and one opposed. Finally, in 1983, the federal government appropriated $42 million to acquire and demolish every building in Centralia. Nearly everyone participated in the voluntary buyouts; by 1990, Census figures showed only 63 people remaining. …

Few remain as 1962 Pa. coal town fire still burns via Apocadocs