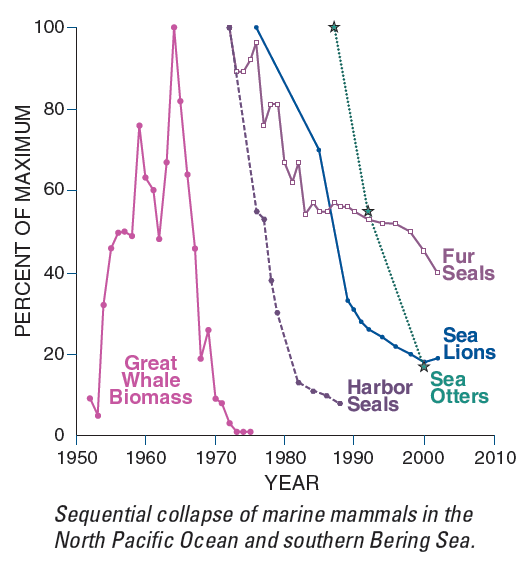

Graph of the Day: Sequential Collapse of Marine Mammals in the North Pacific Ocean and southern Bering Sea

By Gloria Maender

October 2003 The rapid removal of at least half a million great whales from the North Pacific Ocean by intensive industrial whaling more than 50 years ago may have unleashed a complex ecological chain reaction that has since rippled resoundingly from ocean to coastal ecosystems, according to a team of eight scientists, including Jim Estes, a U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) research ecologist and adjunct professor at the University of California, Santa Cruz. The team’s paper on this subject, which prompted articles in newspapers around the country, was published in October in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The scientists believe that when great whales became scarce, their foremost natural predators, killer whales, turned to other marine mammals as primary sources of food, causing sequential declines in southwest Alaska during the 1960s and 1970s of first the harbor seals, followed by northern fur seals, Steller sea lions, and finally, in the 1990s, sea otters, as killer whales “fished down” the food web. “During three decades of research in the Bering Sea and North Pacific Ocean, I watched other scientists struggle to understand the precipitous population declines of northern fur seals, harbor seals, and Steller sea lions, never imagining that my area of research—sea otters and kelp forests—might be affected by these changes,” said Estes. It was the decades of sea-otter research by Estes and colleagues that ultimately shed light on the pinniped declines. In about 1990, the Aleutian sea-otter population Estes studied plummeted, from an estimated 55,000-100,000 individuals in the 1980s to 6,000 individuals in 2000. “By the late 1990s, sea otters occurred at such a low density throughout the archipelago that sea urchins were overgrazing the kelp forest,” said Estes. …

Collapsing Populations of Marine Mammals—the North Pacific’s Whaling Legacy? [pdf]